Metabolic FLIM of

Macroscopic Objects

Wolfgang Becker, Lukas Braun, Julius Heitz, Becker &

Hickl GmbH, Berlin

Vladislav

Shcheslavskiy, Marina Shirmanova, Privolzhski Research Medical University, Nizhniy

Novgorod

Abstract: Fluorescence lifetime images of macroscopic

samples as large as 20 mm can be recorded in the primary focal plane of

the DCS‑120 confocal scanner. The system can be used for measuring metabolic

parameters of biological tissue. Metabolic FLIM is performed via the

fluorescence decay parameters of NAD(P)H and thus requires an excitation

wavelength of 375 nm or shorter. Commonly used lens elements have poor

transmission and large chromatic aberration at this wavelength. We therefore

replaced the standard scan lens with one that consists of a combination of UV

achromats. This increases the efficiency of the system by 40%. The spatial

resolution is about 15 µm, images can be recorded with pixel numbers as

large as 2048 x 2048. Acquisition times range from a few seconds for

imaging with low pixel number and moderate lifetime accuracy to a few minutes

for mega-pixel images and ultra-high accuracy of the decay data. We demonstrate

the use of the system for metabolic imaging of a tumor in a mouse and of

glioblastoma in a rat brain.

Motivation

FLIM, especially TCSPC FLIM, is usually

associated with imaging through a laser scanning microscope [2, 3]. A laser

beam is sent down the beam path of the microscope, and scanned around a pivot

point located in the principle plane of the microscope lens. The fluorescence

light is collected back through the microscope lens and the scanner, separated

from the excitation light by a dichroic mirror, and detected through a pinhole [3, 4]. Microscopes are usually limited to an

image size of no more than 500 x 500 µm. To perform FLIM of

larger objects bh have introduced the DCS-120 MACRO system [3, 4]. Instead of imaging

through a microscope, this system scans the object directly in the image plane

of the scanner. An example is shown in Fig. 1.

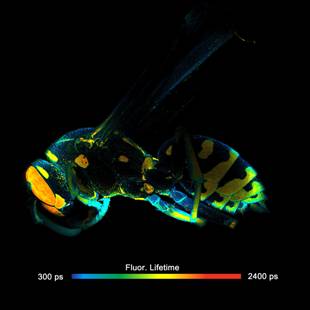

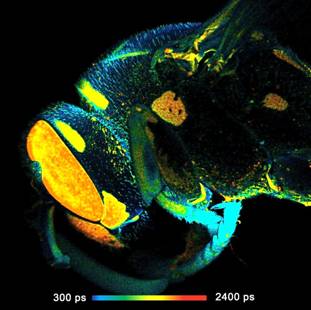

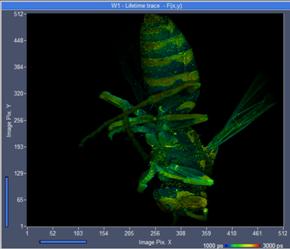

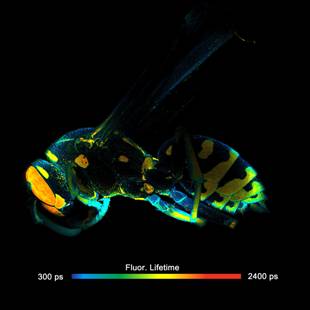

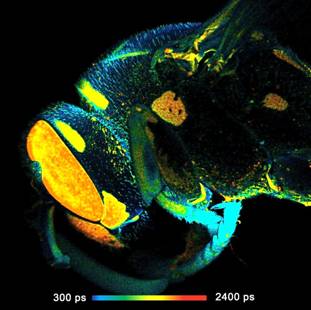

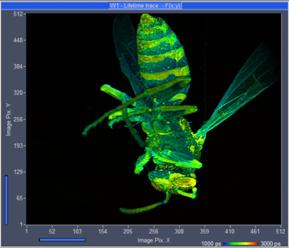

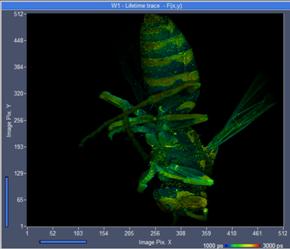

Fig. 1: FLIM of a wasp recorded in the primary image plane of a bh DCS-120

scanner. 2048x2048 pixels, 256 time channels. Left: Full-size scan, field

diameter 18 mm. Right: A digital zoom into the image shown left gives an

impression of the spatial resolution on the data.

Principle

The optical principle of the DCS-MACRO system is shown in Fig. 2. The

angle of the laser beam is scanned by two fast-moving galvanometer mirrors. The

scan lens focuses the laser beam into an image plane shortly in front of the

scanner, and simultaneously transfers the angular motion of the beam into a

lateral motion in this plane [4].

Fig. 2: Left:

Principle of the DCS-120 scanner for imaging macroscopic objects. Right: Photo

of the system.

The focused laser beam excites fluorescence

at the surface of the sample or slightly below. The fluorescence light is collected

and collimated by the scan lens, de-scanned by the galvanometer mirrors, and separated

from the excitation light by the main dichroic beamsplitter. The fluorescence

beam is further split into two spectral or polarisation components, and focused

into pinholes. Only light that comes from the focal plane of the excitation

beam can pass the pinholes efficiently. The pinholes thus suppress light that

is scattered in the sample or excited outside the focal plane. Photons passing

the pinholes is sent to the detectors [5, 6] through bandpass filters. FLIM data

are built up from the times and locations of the photons by multi-dimensional

TCSPC [2, 3].

In fact, Fig. 2 describes the known

operation principle of a confocal scanner [3, 4]. It is the same as for a scanner

attached to a microscope, with the difference that the microscope and thus the magnification

by its objective lens is left off. The relative resolution of the images, i.e.

the ratio of field diameter to the size of the point-spread function is the

same as in combination with a microscope. A full-size images can, in principle,

reasonably be scanned with 2048 x 2048 pixels. That means, images

recorded in the scanner image plane can be amazingly rich in detail, as can be

seen in Fig. 1. Acquisition

times range from a few seconds for imaging with low pixel number and moderate

lifetime accuracy to a few minutes for mega-pixel images and ultra-high

accuracy of the decay data.

Metabolic FLIM

Metabolic imaging by TCSPC FLIM has an

enormous potential for cancer detection [18, 30], investigation of cancer

origins and cancer progression [17, 19, 23,], and evaluation of the response of

cells and tissues to anti-cancer drugs [16, 22, 24, 29].

Metabolic imaging is performed best by FLIM

of NAD(P)H (nicotinamide adenine (pyridine) dinucleotide). It is known that the

fluorescence decay function of NAD(P)H depends on the binding to proteins [12, 13, 20]. Unbound NAD(P)H has a fluorescence

lifetime of about 0.3 to 0.5 ns, bound NAD(P)H has a lifetime of

1.2 ns to 3.5 ns [13].

The ratio of the amounts of bound and unbound NAD(P)H depends on the type of

the metabolism. A cell can run both a reductive metabolism (glycolysis) and an

oxidative one (oxidative phosphorylation). A shift from glycolysis to oxidative

phosphorylation or back results in a change in the unbound/bound ratio. Thus,

the bound/unbound ratios reflect the Warburg Effect: In normal cells oxidative phosphorylation dominates, in cancer

cells reductive glycolysis [31, 32].

Spectral separation of the signals from

bound and unbound NAD(P)H is difficult, if not impossible. In FLIM data, however,

the signals can be separated by double-exponential decay analysis [3, 7]. The amplitude of the fast component, a1

('metabolic indicator'), or the ratio of the amplitudes of the decay

components, a1/a2, (metabolic ratio), directly represent the concentration

ratio of unbound/bound NAD(P)H and thus characterises the metabolic state of

the tissue [3, 9, 10, 21, 27]. Having a large field of view can be extremely

useful in these applications. The cell metabolism in a large piece of tissue

stays intact for a longer period of time than in a thin tissue slice, post-surgery

material can better be inspected for completeness of tumor excision, tumors can

be investigated in their natural environment, and the effect of a tumor on the

surrounding tissue can be studied.

UV Operation of the Scanner

A problem of NAD(P)H FLIM is the short

excitation wavelength. For efficient excitation a wavelength in the range from

340 nm to 375 nm is required. Optics made of the traditional crown and

flint glasses or of the modern replacements of them have poor transmission in

this wavelength range. This is not a severe problem when the scanner is used in

combination with a microscope. The laser power is then limited by the

photostability of the sample. The applicable power is far below the maximum

power of a picosecond diode laser, so that some loss in the excitation path can

easily be tolerated.

For a macro scanner the situation is

different. The numerical aperture of the detection beam path is much smaller

than in a microscope. That means the collection efficiency is lower. Low

detection efficiency must be compensated by high excitation power. Different

than in a microscope, high power it not a problem for the sample because it is

distributed over a large scan area. Unfortunately, the power of a picosecond

diode laser is limited to a few mW. It is therefore important to minimise the

losses of the laser on its way from the scanner input to the sample. We

therefore designed a scan lens from novel UV-transparent glass types which

recently became available. A comparison of the image intensity obtained with new

UV scan lens compared to the normal VIS lens is given in Fig. 3. A FLIM image

recorded with the UV lens is shown left, an image recorded with the VIS lens is

shown right. The recorded intensity is 40% higher with the UV lens.

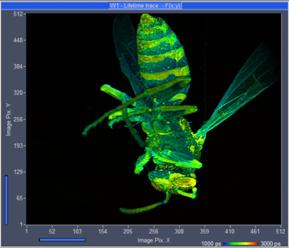

Fig. 3: FLIM of

a wasp, excitation 375 nm. Recorded with the UV lens (left) and image recorded

with the VIS lens (right)

Results

Tumor in a Mouse

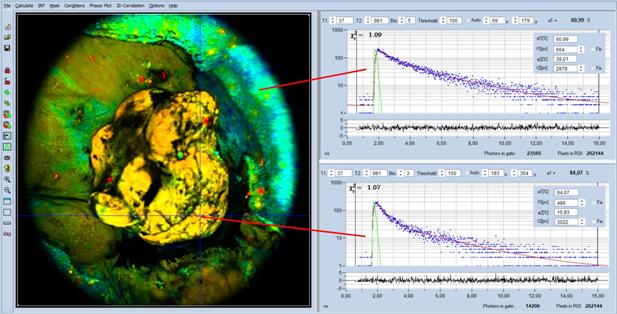

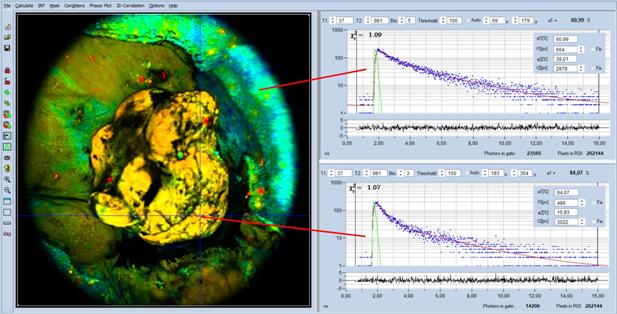

Fig. 4 shows a FLIM image of a tumor in a

mouse. The skin was removed over the tumor to provide direct optical access to

the tumor tissue. The data were analysed with SPCImage NG [3, 7]. A

double-exponential model was used, the image parameter is the amplitude, a1, of

the fast decay component.

Fig. 4: Macro-FLIM data of an open tumor in a mouse. Analysis with

SPCImage, double-exponential analysis, image parameter is the amplitude, a1, of

the fast decay component. Decay curves in the non-tumor and in the tumor region

shown on the right.

Decay curves in the non-tumor and in the

tumor region are shown on the right. Visibly, the decay curve in the tumor

region (lower curve) appears steeper than the curve in the non-tumor region

(upper curve). The decay parameters (see insert in the curve) show the effect

quantitatively: The amplitude, a1, in the tumor region is higher than in the

non-tumor region. The a1 values are 84% and 61%, respectively. This is exactly

what has to be expected: The amount of free NAD(P)H is higher in the tumor [3].

The result is perfectly compatible with [10] and [27], where the transition

from non-tumor to tumor was found at an a1 of about 70%.

Glioblastoma

Almost all types of tumor cells and tumor

tissues investigated so far show identical behaviour: A tumor has an increase

in a1, showing that there is more unbound NAD(P)H than in healthy tissue [3]. No

so glioblastoma. Either there is no increase in a1 compared to the surrounding

brain tissue, or, in contrast to other tumors, even a decrease in a1. The

reasons of this behaviour are unknown. Of course, one may just accept that

glioblastoma are in some way special. However, it is hard to believe that

glioblastoma should have no metabolic shift toward glycolysis, or that this

shift should not be reflected by an increase of unbound NAD(P)H. We therefore

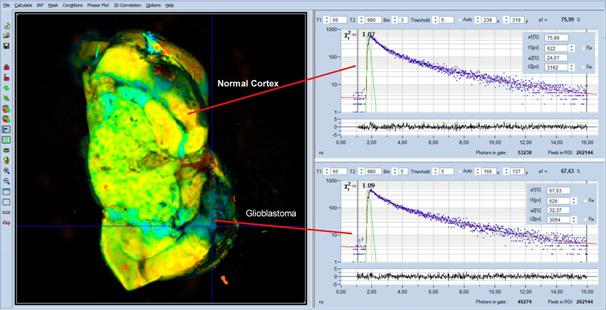

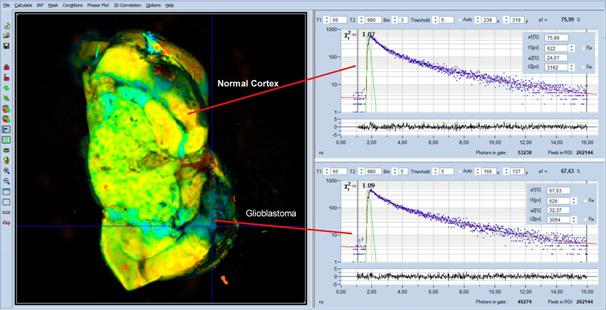

performed macroscopic FLIM measurement on excised rat brains that contained

glioblastoma, see [18] for details. An example is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5: MACRO-FLIM image of a rat brain with a glioblastoma. The glioblastoma

is the blue area in the lower right of the image. Decay curves from a healthy

region and from the tumor region are shown upper and lower right.

The glioblastoma is the blue area in the

lower right of the image. Decay curves from a healthy region and from the tumor

region are shown upper and lower right. Decay parameters are shown as inserts

in the decay curves. Indeed, the tumor has a lower a1 than the healthy tissue:

In the tumor a1 is 67%, compared to 76% in the surrounding brain tissue.

We can exclude simple instrumental

artefacts or mistakes in the measurement procedure as a source of the effect.

The data quality is excellent, as the decay curves in Fig. 5 show. A common

mistake is detection of FAD instead of NAD(P)H. FAD can be excited at the same

wavelength as NAD(P)H, and exhibits an opposite metabolic effect in a1 as

NAD(P)H. However, we used an emission filter which blocked wavelengths above 475 nm.

Accidental detection of FAD can therefore be excluded.

A hint towards a possible explanation is

the large a1 which is observed in the healthy regions. With a1 = 76%

it is in fact far in the region which is typical for tumors. Is the high a1 a

general feature of brain tissue? Is it possible that in fact a1 in the normal

regions is too high, and not the a1 in the tumor too low? This could

potentially reverse the a1 effect.

A possible reason of high a1 could be the

high metabolic activity of the brain cortex. The high energetic and

biosynthetic demands of neurons and astrocytes in the brain tissue shift its

metabolism toward glycolysis, accompanied by an increase in a1. Unlike the cortex,

the white matter, which is composed of myelinated nerve fibres, typically has

lower a1 than glioma, please see [33]. It can also not be excluded that the

excised brain tissue runs into hypoxia. It would then shift its metabolism

toward glycolysis, accompanied by an increase in a1. The only way to avoid this

is to drastically reduce the time from excising the brain to the FLIM

recording, or to record FLIM directly in the rat, either through a cranial

window [1] or through an optical fibre [15].

Possible Extensions

The system can be extended to detect FAD

simultaneously with NAD(P)H. Two lasers, one for excitation of NAD(P)H and the

other for FAD are multiplexed synchronously with the lines or frames of the

scan, and the emission signals detected by two detectors and two parallel TCSPC

FLIM channels [9]. The corresponding control functions are implemented in the

scan controller and in the SPCM data acquisition software [3, 4].

Laser multiplexing can also be used to

record NAD(P)H FLIM simultaneously with FLIM of an exogenous fluorophore. This

fluorophore may be used to detect changes in pH [26], concentration of special

ions, protein conformation, local viscosity, or another molecular parameter [28].

Another extension is simultaneous recording

of FLIM and PLIM (phosphorescence lifetime images) [8]. FLIM is then used to determine the

metabolic state, PLIM to determine the oxygen partial pressure in the tissue [11,

25]. Also these functions are implemented in the DCS-MACRO standard systems.

Please see [3, 4].

Summary

The bh DCS-120 MACRO system detects FLIM

from objects as large as 20 mm in diameter. The sensitivity of the system

at excitation wavelengths in the near-UV region has been significantly

increased by a new scan lens consisting of novel UV transmitting glass types. A

375-nm picosecond diode laser is used to excite fluorescence of NAD(P)H. The

fluorescence is detected by high-speed high sensitivity hybrid detectors and

recorded by multi-dimensional TCSPC. The spatial resolution of the images is

about 15 µm, pixel numbers can be as large as 2048 x 2048. We

have shown the performance of the system for recording metabolic FLIM of a

tumor in a mouse and of glioblastoma in a rat brain. The data are analysed with

SPCImage NG. Double exponential decay analysis delivers the amplitude of the

fast decay component, a1, which is a direct indicator of the metabolic state of

the tissue.

References

1.

B. J. Bacskai, J. Skoch, G.A. Hickey, O.

Berezovska, B.T. Hyman, Multiphoton imaging in mouse models of Alzheimers

disease, Proc. SPIE, 5323, 71-76 (2004)

2. W. Becker, Advanced time-correlated single-photon counting techniques. Springer,

Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 2005

3.

W. Becker, The bh TCSPC handbook. 9th edition,

Becker & Hickl GmbH (2021), available on www.becker-hickl.com. Please contact bh for printed

copies.

4. Becker & Hickl GmbH, DCS-120 Confocal Scanning FLIM Systems. User

handbook. www.becker-hickl.com

5. Becker & Hickl GmbH, The HPM‑100-40 Hybrid Detector.

Application note, available on www.becker-hickl.com

6. Becker & Hickl GmbH, Sub-20ps IRF Width from Hybrid Detectors

and MCP-PMTs. Application note, available on www.becker-hickl.com

7.

Becker & Hickl GmbH, SPCImage next

generation FLIM data analysis software. Overview

brochure, available on www.becker-hickl.com

8. Becker & Hickl GmbH, Simultaneous Phosphorescence and

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging by Multi-Dimensional TCSPC and Multi-Pulse

Excitation. Application note, available on www.becker-hickl.com

9. W. Becker, A. Bergmann, L. Braun, Metabolic Imaging with the DCS-120

Confocal FLIM System: Simultaneous FLIM of NAD(P)H and FAD, Application note,

available on www.becker-hickl.com (2018)

10. W. Becker, R. Suarez-Ibarrola, A. Miernik, L. Braun, Metabolic

Imaging by Simultaneous FLIM of NAD(P)H and FAD. Current Directions in

Biomedical Engineering 5(1), 1-3 (2019)

11. S. Kalinina, V. Shcheslavskiy, W. Becker, J. Breymayer, P. Schäfer,

A. Rück, Correlative NAD(P)H-FLIM and oxygen sensing-PLIM for metabolic

mapping. J. Biophotonics 9(8):800-811 (2016)

12. J.R. Lakowicz, H. Szmacinski, K. Nowaczyk, M.L. Johnson,

Fluorescence lifetime imaging of free and protein-bound NADH, PNAS 89,

1271-1275 (1992)

13. J.R. Lakowicz, Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd edn.,

Springer (2006)

14. M.N. Pastore, H. Studier, C.S. Bonder, M.S. Roberts, Non-invasive

metabolic imaging of melanoma progression. Exp. Dermatol. 26, 607614 (2017)

15. M. Lukina, A. Orlova, M. Shirmanova, D.

Shirokov, A. Pavlikov, A. Neubauer, H. Studier, W. Becker, E. Zagaynova, T.

Yoshihara, S. Tobita, V. Shcheslavskiy, Interrogation of metabolic and oxygen

states of tumors with fiber-based luminescence lifetime spectroscopy. Optics Letters 42(4)

731-734 (2017)

16. M. M. Lukina, V. V. Dudenkova, N. I. Ignatovaa, I. N. Druzhkova, L.

E. Shimolina, E. V. Zagaynovaa, M. V. Shirmanova, Metabolic cofactors NAD(P)H

and FAD as potential indicators of cancer cell response to chemotherapy with

paclitaxel. BBA General Subjects 1862, 1693-1700 (2018)

17. M. M. Lukina, L. E. Shimolina, N. M. Kiselev, V. E. Zagainov, D. V.

Komarov, E. V. Zagaynova, M. V. Shirmanova, Interrogation of tumor metabolism

in tissue samples ex vivo using fluorescence lifetime imaging of NAD(P)H.

Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 8, 014002, 1-11 (2020)

18. M. Lukina, K. Yashin, E. E. Kiseleva, A. Alekseeva, Varvara

Dudenkova, E. V. Zagaynova, E. Bederina, I. Medyanic, W. Becker, D. Mishra, M.

Berezin, V. I. Shcheslavskiy, M. Shirmanova, Label-Free Macroscopic

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Brain Tumors. Frontiers in Oncology 11,

666059, 1-11 (2021)

19. M.N. Pastore, H. Studier, C.S. Bonder, M.S. Roberts, Non-invasive

metabolic imaging of melanoma progression. Exp. Dermatol. 26, 607614 (2017)

20. R.J. Paul, H. Schneckenburger, Oxygen concentration and the

oxidation-reduction state of yeast: Determination of free/bound NADH and

flavins by time-resolved spectroscopy, Naturwissenschaften 83, 32-35 (1996)

21. P. M. Schaefer, S. Kalinina, A. Rueck, C.A.F. von Arnim, B. von

Einem, NADH Autofluorescence - A Marker on its Way to Boost Bioenergetic

Research. Cytometry Part A, 1-13 (2018)

22. A.T. Shah, K.E. Diggins, A.J. Walsh, J.M. Irish, M.C. Skala, In vivo

autofluorescence imaging of tumor heterogeneity in response to treatment.

Neoplasia 17, 862-870 (2015)

23. M. C. Skala, K. M. Riching, D. K. Bird, A. Dendron-Fitzpatrick, J.

Eickhoff, K. W. Eliceiri, P. J. Keely, N. Ramanujam, In vivo multiphoton

fluorescence lifetime imaging of protein-bound and free nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide in normal and precancerous epithelia. J. Biomed. Opt. 12 02401-1

to 10 (2007)

24. A. A. Gillette, C. P. Babiarz, A. R. Van Dommelen, C. A. Pasch, L.

Clipson, K. A. Matkowskyj, D. A. Deming, M. C. Skala, Autofluorescence Imaging

of Treatment Response in Neuroendocrine Tumor Organoids. Cancers (Basel).

13(8), 1873, 1-17 (2021)

25. Y. P. Parshina, A. D. Komarova, L. N. Bochkarev, T. A. Kovylina, A.

A. Plekhanov, L. G. Klapshina, A. N. Konev, A. M. Mozherov, I. D. Shchechkin, M.

A. Sirotkina, V. I. Shcheslavskiy, M. V. Shirmanova, Simultaneous Probing of

Metabolism and Oxygenation of Tumors In Vivo Using FLIM of NAD(P)H and PLIM of

a New Polymeric Ir(III) Oxygen Sensor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022) 10263

26. P.M. Schaefer,

D. Hilpert, M. Niederschweiberer, L. Neuhauser, S. Kalinina, E. Calzia, A.

Rueck, B. von Einem, C.A.F. von Arnim, Mitochondrial matrix pH as a decisive

factor in neurometabolic imaging. Neurophotonics

4(4):045004 (2017)

27. R. Suarez-Ibarrola, L. Braun, P. Fabian Pohlmann, W. Becker, A.

Bergmann, C. Gratzke, A. Miernik, K. Wilhelm, Metabolic Imaging of Urothelial

Carcinoma by Simultaneous Autofluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) of NAD(P)H

and FAD. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer (2020)

28. K. Suhling, L. M. Hirvonen, J. A. Levitt, P.-H. Chung, C. Tregido,

A. le Marois, D. Rusakov, K. Zheng, Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging

(FLIM): Basic Concepts and Recent Applications. In: W. Becker (ed.)

Advanced time-correlated single photon counting applications. Springer, Berlin,

Heidelberg, New York (2015)

29. A. J. Walsh, R. S. Cook, M. E. Sanders, L. Aurisicchio, G.

Ciliberto, C. L. Arteaga, M. C. Skala, Quantitative Optical Imaging of Primary

Tumor Organoid Metabolism Predicts Drug Response in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res

74, OF1-OF11 (2014)

30. A. J. Walsh, A. T. Shah, J. T. Sharick, M. C. Skala, Fluorescence Lifetime

measurements of NADH in live cells and tissue. In: W. Becker (ed.) Advanced

time-correlated single photon counting applications. Springer, Berlin,

Heidelberg, New York (2015)

31. O. Warburg, On the origin of cancer cells. Science 123, 309-314

(1956)

32. O. Warburg, On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science 124,

269-270 (1956)

33. Yuzhakova D, Kiseleva E, Shirmanova M, Shcheslavskiy V, Sachkova D,

Snopova L, Bederina E, Lukina M, Dudenkova V, Yusubalieva G, Belovezhets T,

Matvienko D, Baklaushev V. Highly Invasive Fluorescent/Bioluminescent

Patient-Derived Orthotopic Model of Glioblastoma in Mice. Front Oncol. 2022 Jul

13;12:897839. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.897839.